Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in muscle tissue.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a type of sarcoma. Sarcoma is cancer of soft tissue (such as muscle), connective tissue (such as tendon or cartilage), or bone. Rhabdomyosarcoma usually begins in muscles that are attached to bones and that help the body move, but it may begin in many places in the body. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma in children.

There are four main types of rhabdomyosarcoma:

- Embryonal: This type occurs most often in the head and neck area or in the genital or urinary organs, but can occur anywhere in the body. It is the most common type of rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Alveolar: This type occurs most often in the arms or legs, chest, abdomen, genital organs, or anal area.

- Spindle cell /sclerosing: The spindle cell type occurs most often in the paratesticular (testis or spermatic cord) area. There are two other spindle cell/sclerosing subtypes. One is more common in infants and is found in the trunk area. The other can affect children, adolescents, and adults. It is often found in the head and neck area, and is more aggressive.

- Pleomorphic: This is the least common type of rhabdomyosarcoma in children.

See the following PDQ treatment summaries for information about other types of soft tissue sarcoma:

- Soft Tissue Sarcoma

- Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Certain genetic conditions increase the risk of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma.

Anything that increases the risk of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn't mean that you will not get cancer. Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Risk factors for rhabdomyosarcoma include having the following inherited diseases:

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

- Dicer1 syndrome.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

- Costello syndrome.

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

- Noonan syndrome.

Children who had a high birth weight or were larger than expected at birth may have an increased risk of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma.

In most cases, the cause of rhabdomyosarcoma is not known.

A sign of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is a lump or swelling that keeps getting bigger.

Signs and symptoms may be caused by childhood rhabdomyosarcoma or by other conditions. The signs and symptoms that occur depend on where the cancer forms. Check with your child's doctor if your child has any of the following:

- A lump or swelling that keeps getting bigger or does not go away. It may be painful.

- Crossed-eyes or bulging of the eye.

- Headache.

- Trouble urinating or having bowel movements.

- Blood in the urine.

- Bleeding in the nose, throat, vagina, or rectum.

Diagnostic tests and a biopsy are used to diagnose childhood rhabdomyosarcoma.

The diagnostic tests that are done depend in part on where the cancer forms. The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient's health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- X-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the body, such as the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the chest, abdomen, pelvis, or lymph nodes, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body. - MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas of the body, such as the skull, brain, and lymph nodes. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged. - PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

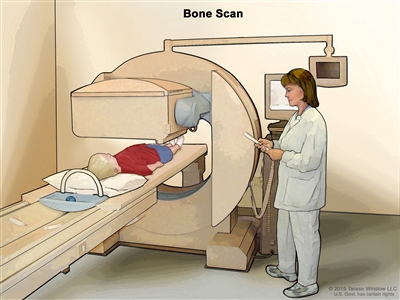

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the PET scanner. The head rest and white strap help the child lie still. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into the child's vein, and a scanner makes a picture of where the glucose is being used in the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up more glucose than normal cells do. - Bone scan: A procedure to check if there are rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells, in the bone. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material collects in the bones with cancer and is detected by a scanner.

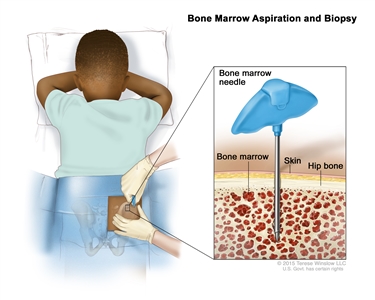

Bone scan. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into the child's vein and travels through the blood. The radioactive material collects in the bones. As the child lies on a table that slides under the scanner, the radioactive material is detected and images are made on a computer screen. - Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: The removal of bone marrow, blood, and a small piece of bone by inserting a hollow needle into the hipbone. Samples are removed from both hipbones. A pathologist views the bone marrow, blood, and bone under a microscope to look for signs of cancer.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. After a small area of skin is numbed, a bone marrow needle is inserted into the child's hip bone. Samples of blood, bone, and bone marrow are removed for examination under a microscope. - Lumbar puncture: A procedure used to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal column. This is done by placing a needle between two bones in the spine and into the CSF around the spinal cord and removing a sample of the fluid. The sample of CSF is checked under a microscope for signs of cancer cells. This procedure is also called an LP or spinal tap.

If these tests show there may be a rhabdomyosarcoma, a biopsy is done. A biopsy is the removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. Because treatment depends on the type of rhabdomyosarcoma, biopsy samples should be checked by a pathologist who has experience in diagnosing rhabdomyosarcoma.

One of the following types of biopsies may be used:

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy: The removal of tissue or fluid using a thin needle.

- Core needle biopsy: The removal of tissue using a wide needle. This procedure may be guided using ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI.

- Open biopsy: The removal of tissue through an incision (cut) made in the skin.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy: The removal of the sentinel lymph node during surgery. The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node in a group of lymph nodes to receive lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor. It is the first lymph node the cancer is likely to spread to from the primary tumor. A radioactive substance and/or blue dye is injected near the tumor. The substance or dye flows through the lymph ducts to the lymph nodes. The first lymph node to receive the substance or dye is removed. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. If cancer cells are not found, it may not be necessary to remove more lymph nodes. Sometimes, a sentinel lymph node is found in more than one group of nodes. Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be used for patients with rhabdomyosarcoma of the limbs or trunk when enlarged lymph nodes are not found with imaging or physical exam.

The following tests may be done on the sample of tissue that is removed:

- Light microscopy: A laboratory test in which cells in a sample of tissue are viewed under regular and high-powered microscopes to look for certain changes in the cells.

- Immunohistochemistry: A laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type of cancer.

- FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization): A laboratory test used to look at and count genes or chromosomes in cells and tissues. Pieces of DNA that contain fluorescent dyes are made in the laboratory and added to a sample of a patient's cells or tissues. When these dyed pieces of DNA attach to certain genes or areas of chromosomes in the sample, they light up when viewed under a fluorescent microscope. The FISH test is used to help diagnose cancer and help plan treatment.

- Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) test: A laboratory test in which the amount of a genetic substance called mRNA made by a specific gene is measured. An enzyme called reverse transcriptase is used to convert a specific piece of RNA into a matching piece of DNA, which can be amplified (made in large numbers) by another enzyme called DNA polymerase. The amplified DNA copies help tell whether a specific mRNA is being made by a gene. RT–PCR can be used to check the activation of certain genes that may indicate the presence of cancer cells. This test may be used to look for certain changes in a gene or chromosome, which may help diagnose cancer.

- Cytogenetic analysis: A laboratory test in which the chromosomes of cells in a sample of tissue are counted and checked for any changes, such as broken, missing, rearranged, or extra chromosomes. Changes in certain chromosomes may be a sign of cancer. Cytogenetic analysis is used to help diagnose cancer, plan treatment, or find out how well treatment is working.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the following:

- The patient's age.

- Where in the body the tumor started.

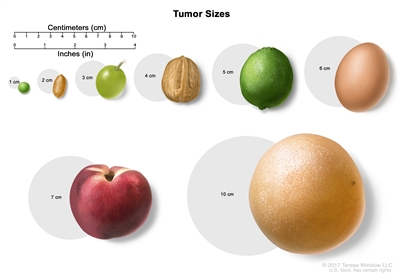

- The size of the tumor at the time of diagnosis.

- Whether the tumor has been completely removed by surgery.

- The type of rhabdomyosarcoma (embryonal, alveolar, spindle cell /sclerosing, or pleomorphic).

- Whether there are certain changes in the genes.

- Whether the tumor had spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis.

- Whether the tumor was in the lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis.

- Whether the tumor responds to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

For patients with recurrent cancer, prognosis and treatment also depend on the following:

- Where in the body the tumor recurred (came back).

- How much time passed between the end of cancer treatment and when the cancer recurred.

- Whether the cancer was previously treated with radiation therapy.

After childhood rhabdomyosarcoma has been diagnosed, treatment is based in part on the stage of the cancer and sometimes it is based on whether all the cancer was removed by surgery.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the tissue or to other parts of the body is called staging. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment. The doctor will use results of the diagnostic tests to help find out the stage of the disease.

Treatment for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is based in part on the stage and sometimes on the amount of cancer that remains after surgery to remove the tumor. The pathologist will use a microscope to check the tissues removed during surgery, including tissue samples from the edges of the areas where the cancer was removed and the lymph nodes. This is done to see if all the cancer cells were taken out during the surgery.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if rhabdomyosarcoma spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually rhabdomyosarcoma cells. The disease is metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, not lung cancer.

Staging of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is done in three parts.

Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is staged by using three different ways to describe the cancer:

- A staging system.

- A grouping system.

- A risk group.

The staging system is based on the size of the tumor, where it is in the body, and whether it has spread to other parts of the body:

Stage 1

In stage 1, the tumor is any size, may have spread to lymph nodes, and is found in only one of the following "favorable" sites:

- Eye or area around the eye.

- Head and neck (but not in the tissue near the ear, nose, sinuses, base of the skull, brain, or spinal cord).

- Gallbladder and bile ducts.

- Ureters or urethra.

- Testes, ovary, vagina, or uterus.

Rhabdomyosarcoma that forms in a "favorable" site has a better prognosis. If the site where cancer occurs is not one of the favorable sites listed above, it is said to be an "unfavorable" site.

Tumor sizes are often measured in centimeters (cm) or inches. Common food items that can be used to show tumor size in cm include: a pea (1 cm), a peanut (2 cm), a grape (3 cm), a walnut (4 cm), a lime (5 cm or 2 inches), an egg (6 cm), a peach (7 cm), and a grapefruit (10 cm or 4 inches).

Stage 2

In stage 2, cancer is found in an "unfavorable" site (any one area not described as "favorable" in stage 1). The tumor is no larger than 5 centimeters and has not spread to lymph nodes.

Stage 3

In stage 3, cancer is found in an "unfavorable" site (any one area not described as "favorable" in stage 1) and one of the following is true:

- The tumor is no larger than 5 centimeters and cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- The tumor is larger than 5 centimeters and cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 4

In stage 4, the tumor may be any size and cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes. Cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lung, bone marrow, or bone.

The grouping system is based on whether the cancer has spread and whether all the cancer was removed by surgery:

Group I

Cancer was found only in the place where it started and it was completely removed by surgery. Tissue was taken from the edges of where the tumor was removed. This tissue was checked under a microscope by a pathologist and no cancer cells were found.

Group II

Group II is divided into groups IIA, IIB, and IIC.

- IIA: Cancer was removed by surgery but cancer cells were seen when the tissue, taken from the edges of where the tumor was removed, was viewed under a microscope by a pathologist.

- IIB: Cancer had spread to nearby lymph nodes and the cancer and lymph nodes were removed by surgery.

- IIC: Cancer had spread to nearby lymph nodes, the cancer and lymph nodes were removed by surgery, and at least one of the following is true:

- Tissue taken from the edges of where the tumor was removed was checked under a microscope by a pathologist and cancer cells were seen.

- The furthest lymph node from the tumor that was removed was checked under a microscope by a pathologist and cancer cells were seen.

Group III

Cancer was partly removed by biopsy or surgery but there is tumor remaining that can be seen with the eye.

Group IV

Cancer had spread to distant parts of the body when the cancer was diagnosed.

- Cancer cells are found by an imaging test; or

- There are cancer cells in the fluid around the brain, spinal cord, or lungs, or in fluid in the abdomen; or tumors are found in those areas.

The risk group is based on the staging system and the grouping system.

The risk group describes the chance that rhabdomyosarcoma will recur (come back). Every child treated for rhabdomyosarcoma should receive chemotherapy to decrease the chance cancer will recur. The type of anticancer drug, dose, and the number of treatments given depends on whether the child has low-risk, intermediate-risk, or high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma.

The following risk groups are used:

Low-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma

Low-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is one of the following:

- An embryonal tumor of any size that is found in a "favorable" site. There may be tumor remaining after surgery that can be seen with or without a microscope. The cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes. The following areas are "favorable" sites:

- Eye or area around the eye.

- Head or neck (but not in the tissue near the ear, nose, sinuses, base of the skull , brain, or spinal cord).

- Gallbladder and bile ducts.

- Ureter or urethra.

- Testes, ovary, vagina, or uterus.

- An embryonal tumor of any size that is not found in a "favorable" site. There may be tumor remaining after surgery that can be seen only with a microscope. The cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Intermediate-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma

Intermediate-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is one of the following:

- An embryonal tumor of any size that is not found in one of the "favorable" sites listed above. There is tumor remaining after surgery, that can be seen with or without a microscope. The cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- An alveolar tumor of any size in a "favorable" or "unfavorable" site. There may be tumor remaining after surgery that can be seen with or without a microscope. The cancer may have spread to nearby lymph nodes.

High-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma

High-risk childhood rhabdomyosarcoma may be the embryonal type or the alveolar type. It may have spread to nearby lymph nodes and has spread to one or more of the following:

- Other parts of the body that are not near where the tumor first formed.

- Fluid around the brain or spinal cord.

- Fluid in the lung or abdomen.

Sometimes childhood rhabdomyosarcoma continues to grow or comes back after treatment.

Progressive rhabdomyosarcoma is cancer that continues to grow, spread, or get worse. Progressive disease may be a sign that the cancer has become refractory to treatment.

Recurrent childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the same place or in other parts of the body, such as the lung, bone, or bone marrow. Less often, rhabdomyosarcoma may come back in the breast in adolescent females or in the liver.

There are different types of treatment for patients with childhood rhabdomyosarcoma.

Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment.

Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Children with rhabdomyosarcoma should have their treatment planned by a team of health care providers who are experts in treating cancer in children.

Because rhabdomyosarcoma can form in many different parts of the body, many different kinds of treatments are used. Treatment will be overseen by a pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with rhabdomyosarcoma and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. These may include the following specialists:

- Pediatrician.

- Pediatric surgeon.

- Radiation oncologist.

- Pediatric hematologist.

- Pediatric radiologist.

- Pediatric nurse specialist.

- Geneticist or cancer genetics risk counselor.

- Social worker.

- Rehabilitation specialist.

Three types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery (removing the cancer in an operation) is used to treat childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. A type of surgery called wide local excision is often done. A wide local excision is the removal of tumor and some of the tissue around it, including the lymph nodes. A second surgery may be needed to remove all the cancer. Whether surgery is done and the type of surgery done depends on the following:

- Where in the body the tumor started.

- The effect the surgery will have on the way the child will look.

- The effect the surgery will have on the child's important body functions.

- How the tumor responded to chemotherapy or radiation therapy that may have been given first.

In most children with rhabdomyosarcoma, it is not possible to remove all of the tumor by surgery.

Rhabdomyosarcoma can form in many different places in the body and the surgery will be different for each site. Surgery to treat rhabdomyosarcoma of the eye or genital areas is usually a biopsy. Chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation therapy, may be given before surgery to shrink large tumors.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, patients will be given chemotherapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Radiation therapy may also be given. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Certain ways of giving radiation therapy can help keep radiation from damaging nearby healthy tissue. These types of external radiation therapy include the following:

- Conformal radiation therapy: Conformal radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy that uses a computer to make a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shapes the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): IMRT is a type of 3-dimensional (3-D) radiation therapy that uses a computer to make pictures of the size and shape of the tumor. Thin beams of radiation of different intensities (strengths) are aimed at the tumor from many angles.

- Volumetrical modulated arc therapy (VMAT): VMAT is type of 3-D radiation therapy that uses a computer to make pictures of the size and shape of the tumor. The radiation machine moves in a circle around the patient once during treatment and sends thin beams of radiation of different intensities (strengths) at the tumor. Treatment with VMAT is delivered faster than treatment with IMRT.

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy: Stereotactic body radiation therapy is a type of external radiation therapy. Special equipment is used to place the patient in the same position for each radiation treatment. Once a day for several days, a radiation machine aims a larger than usual dose of radiation directly at the tumor. By having the patient in the same position for each treatment, there is less damage to nearby healthy tissue. This procedure is also called stereotactic external-beam radiation therapy and stereotaxic radiation therapy.

- Proton beam radiation therapy: Proton-beam therapy is a type of high-energy, external radiation therapy. A radiation therapy machine aims streams of protons (tiny, invisible, positively-charged particles) at the cancer cells to kill them. This type of treatment may cause less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. It is used to treat cancer in areas such as the vagina, vulva, uterus, bladder, prostate, head, or neck. Internal radiation therapy is also called brachytherapy, internal radiation, implant radiation, or interstitial radiation therapy. This approach involves special technical skills and is offered in only a few medical centers.

The type and amount of radiation therapy and when it is given depends on the age of the child, the type of rhabdomyosarcoma, where in the body the tumor started, how much tumor remained after surgery, and whether there is tumor in the nearby lymph nodes.

External radiation therapy is usually used to treat childhood rhabdomyosarcoma but in certain cases internal radiation therapy is used.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy).

Chemotherapy may also be given to shrink the tumor before surgery in order to save as much healthy tissue as possible. This is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Every child treated for rhabdomyosarcoma should receive systemic chemotherapy to decrease the chance the cancer will recur. The type of anticancer drug, dose, and the number of treatments given depends on the age of the child and whether the child has low-risk, intermediate-risk, or high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma.

See Drugs Approved for Rhabdomyosarcoma for more information.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

This summary section describes treatments that are being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied. Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient's immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body's natural defenses against cancer. This cancer treatment is a type of biologic therapy. There are different types of immunotherapy:

- Vaccine therapy is a cancer treatment that uses a substance or group of substances to stimulate the immune system to find the tumor and kill it. Vaccine therapy is being studied to treat metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy uses the body's immune system to kill cancer cells. Two types of immune checkpoint inhibitors are being studied in the treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma that has come back after treatment:

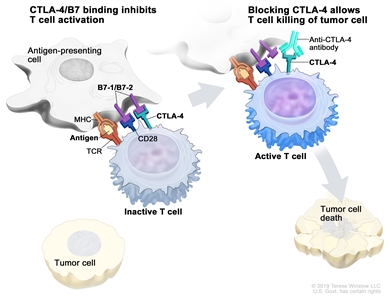

- CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is being studied in the treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma that has come back or progressed during treatment.

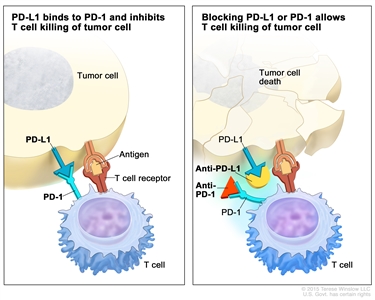

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as B7-1/B7-2 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CTLA-4 on T cells, help keep the body's immune responses in check. When the T-cell receptor (TCR) binds to antigen and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on the APC and CD28 binds to B7-1/B7-2 on the APC, the T cell can be activated. However, the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 keeps the T cells in the inactive state so they are not able to kill tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) allows the T cells to be active and to kill tumor cells (right panel). - PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor therapy: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. PD-L1 is a protein found on some types of cancer cells. When PD-1 attaches to PD-L1, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors keep PD-1 and PD-L1 proteins from attaching to each other. This allows the T cells to kill cancer cells. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are types of PD-1 inhibitors that are being studied in the treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma that has come back or progressed during treatment.

- CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is being studied in the treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma that has come back or progressed during treatment.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, help keep immune responses in check. The binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 keeps T cells from killing tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1) allows the T cells to kill tumor cells (right panel).

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do. There are different types of targeted therapy:

- mTOR inhibitors stop the protein that helps cells divide and survive. Sirolimus is a type of mTOR inhibitor therapy being studied in the treatment of recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma.

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors block signals that cancer cells need to grow and divide. MK-1775, cabozantinib-s-malate, and palbociclib are tyrosine kinase inhibitors being studied in the treatment of newly diagnosed or recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma.

Treatment for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma may cause side effects.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Side effects from cancer treatment that begin after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment for rhabdomyosarcoma may include:

- Physical problems that affect the following:

- Teeth, eye, or gastrointestinal function.

- Fertility (ability to have children).

- Changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory.

- Second cancers (new types of cancer).

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the effects cancer treatment can have on your child and the types of symptoms to expect after cancer treatment has ended. (See the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for more information.)

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI's clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some tests that were done to diagnose or stage the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

The treatment of newly diagnosed childhood rhabdomyosarcoma often includes surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. The order that these treatments are given depends on where in the body the tumor started, the size of the tumor, the type of tumor, and whether the tumor has spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. See the Treatment Option Overview section of this summary for more information about surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy used to treat children with rhabdomyosarcoma.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the brain and head and neck

- For tumors of the brain: Treatment may include surgery to remove the tumor, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

- For tumors of the head and neck that are in or near the eye: Treatment may include chemotherapy and radiation therapy. If the tumor remains or comes back after treatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy, surgery to remove the eye and some tissues around the eye may be needed.

- For tumors of the head and neck that are near the ear, nose, sinuses, or base of the skull but not in or near the eye: Treatment may include radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

- For tumors of the head and neck that are not in or near the eye and not near the ear, nose, sinuses, or base of the skull: Treatment may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery to remove the tumor.

- For tumors of the head and neck that cannot be removed by surgery: Treatment may include chemotherapy and radiation therapy including stereotactic body radiation therapy.

- For tumors of the larynx (voice box): Treatment may include chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgery to remove the larynx is usually not done, so that the voice is not harmed.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the arms or legs

- Chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove the tumor. If the tumor was not completely removed, a second surgery to remove the tumor may be done. Radiation therapy may also be given.

- For tumors of the hand or foot, radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be given. The tumor may not be removed because it would affect the function of the hand or foot.

- Lymph node dissection (one or more lymph nodes are removed and a sample of tissue is checked under a microscope for signs of cancer).

- For tumors in the arms, lymph nodes near the tumor and in the armpit area are removed.

- For tumors in the legs, lymph nodes near the tumor and in the groin area are removed.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis

- For tumors in the chest or abdomen (including the chest wall or abdominal wall): Surgery (wide local excision) may be done. If the tumor is large, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are given to shrink the tumor before surgery.

- For tumors of the pelvis: Surgery (wide local excision) may be done. If the tumor is large, chemotherapy is given to shrink the tumor before surgery. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- For tumors of the diaphragm: A biopsy of the tumor is followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy to shrink the tumor. Surgery may be done later to remove any remaining cancer cells.

- For tumors of the gallbladder or bile ducts: A biopsy of the tumor is followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgery may be done later to remove any remaining cancer cells.

- For tumors of the muscles or tissues around the anus or between the vulva and the anus or the scrotum and the anus: Surgery may be done to remove as much of the tumor as possible and some nearby lymph nodes, followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the kidney

- For tumors of the kidney: Surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy may also be given.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the bladder or prostate

- For tumors that are only at the top of the bladder: Surgery (wide local excision) is done.

- For tumors of the prostate or bladder (other than the top of the bladder):

- Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are given first to shrink the tumor. If cancer cells remain after chemotherapy and radiation therapy, the tumor is removed by surgery. Surgery may include removal of the prostate, part of the bladder, or pelvic exenteration without removal of the rectum. (This may include removal of the lower colon and bladder. In girls, the cervix, vagina, ovaries, and nearby lymph nodes may be removed).

- Chemotherapy is given first to shrink the tumor. Surgery to remove the tumor, but not the bladder or prostate, is done. Internal or external radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- Surgery to remove the tumor, but not the bladder or prostate. Internal radiation therapy is given after surgery.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the area near the testicles

- Surgery to remove the testicle and spermatic cord. The lymph nodes in the back of the abdomen may be checked for cancer, especially if the lymph nodes are large. Patients older than 10 years with no sign of enlarged lymph nodes in the back of the abdomen should have a nerve-sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.

- Radiation therapy may be given if the tumor cannot be completely removed by surgery.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the vulva, vagina, uterus, or ovary

- For tumors of the vulva and vagina: Treatment may include chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove the tumor. Internal or external radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- For tumors of the uterus: Treatment may include chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Sometimes surgery may be needed to remove any remaining cancer cells.

- For tumors of the ovary: Treatment may include chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove any remaining tumor.

Clinical Trials For Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma

- A clinical trial of combination chemotherapy with or without temsirolimus.

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy with cabozantinib-s-malate.

Metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma

Treatment, such as chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy or surgery to remove the tumor, is given to the site where the tumor first formed. If the cancer has spread to the brain, spinal cord, or lungs, radiation therapy may also be given to the sites where the cancer has spread.

The following treatment is being studied for metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma:

- A clinical trial of immunotherapy (vaccine therapy).

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment options for progressive or recurrent childhood rhabdomyosarcoma are based on many factors, including where in the body the cancer has come back, what type of treatment the child had before, and the needs of the child.

Treatment of progressive or recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma may include one or more of the following:

- Surgery.

- Radiation therapy.

- Chemotherapy.

- A clinical trial of combination chemotherapy with or without temsirolimus.

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy or immunotherapy (sirolimus, ipilimumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab).

- A clinical trial of targeted therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (MK-1775, cabozantinib-s-malate, or palbociclib) and chemotherapy.

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

- New therapies being studied in early stage clinical trials should be considered for patients with recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

For more information from the National Cancer Institute about childhood rhabdomyosarcoma, see the following:

- Soft Tissue Sarcoma Home Page

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scans and Cancer

- Drugs Approved for Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer

- Targeted Cancer Therapies

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, visit:

- About Cancer

- Childhood Cancers

- CureSearch for Children's Cancer

- Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer

- Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

- Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents

- Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- Staging

- Coping with Cancer

- Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer

- For Survivors and Caregivers

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government's center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/patient/rhabdomyosarcoma-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389279]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's E-mail Us.

Last Revised: 2022-04-08

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.