Gastrointestinal Complications: Supportive care - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

Constipation is the slow movement of stool (poop) through the large intestine. The longer it takes for the stool to move through the large intestine, the more it loses fluid and the drier and harder it becomes.

If you are constipated, you may be unable to have a bowel movement, need to push harder to have a bowel movement, or have fewer than your usual number of bowel movements. Talk to your doctor if you have constipation. Your doctor can recommend medicines and other ways for treating constipation caused by cancer and cancer treatment.

Constipation may last for a short time, or it may be chronic and last for a long time. Long-term (chronic) constipation can lead to fecal impaction or bowel obstruction, two potentially life-threatening conditions that require immediate medical care. Learn more at What is fecal impaction? and Bowel Obstruction.

What are signs and symptoms of constipation?

Signs and symptoms of constipation include:

- having two or fewer bowel movements in one week

- dry, hard, or lumpy stool

- pain during a bowel movement

- difficulty having a bowel movement

- stomach pain or cramps

- feeling bloated or nauseous

What causes constipation in people with cancer?

Constipation in people with cancer may be caused by:

- Certain types of cancer. Constipation may be a sign or symptom of cancers that push on organs in the abdomen, block the movement of stool through the bowel, or affect the nerves in your spine connected to your bowel. Some cancers that may cause constipation include colon cancer, rectal cancer, ovarian cancer, and brain tumors.

- Cancer treatments such as chemotherapy. Constipation is a common side effect of some types of chemotherapy.

- Medicines. Many medicines, including opioid pain medications, antianxiety drugs, antinausea drugs (antiemetics), and diuretics, can cause constipation.

- Lifestyle and dietary changes. When you are getting cancer treatment, you may have less energy for exercise and your appetite and diet may change. Being less active and eating different foods than normal can cause constipation.

How is constipation diagnosed in people with cancer?

Finding the cause of constipation is important so you can get relief and avoid serious problems such as fecal impaction. Your doctor will do a physical exam, which will include looking at and feeling the abdomen for areas of swelling or firmness and listening to the sounds of your bowels. Your doctor may also ask questions such as:

- How often do you have a bowel movement? How often did you have a bowel movement before you had cancer? Has there been a recent change in your bowel habits?

- When was your last bowel movement? What was it like (how much, hard or soft, what color, was there blood)? Did you have to push more than usual?

- Do you have a fever, cramps, a feeling of fullness near the rectum, pain, or bloating?

Your doctor may be able to diagnose constipation and suggest treatment based on a physical exam and these questions. Sometimes, your doctor may need to do other tests to better understand what is causing constipation:

- Digital rectal examination (DRE): A physical exam in which the doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for impacted stool or unusual changes.

- X-rays: An x-ray is a type of radiation that, in low doses, can be used to make a picture of areas inside the body. An x-ray of the abdomen can show a tumor or fecal impaction that may be causing constipation.

Ways to prevent and treat constipation

If your doctor thinks your cancer or cancer treatments will cause constipation, they will give you tips and prescribe medicine to prevent it. If you become constipated, your doctor will recommend many of these same tips and medicines to help you get relief. Talk with your health care team about what treatment is right for you.

Tips for managing constipation

- Drink plenty of liquids. Drinking 8 cups of water or clear liquids per day can help you stay hydrated, which helps with constipation. Beverages such as coffee and prune juice can have a laxative effect, and hot drinks can also help stool move through the bowel.

- Try to be active every day. Ask your health care team about exercises you can do. Walking, riding a bike, and practicing yoga may be options for you. You can also do light exercise in a bed or chair.

- Eat at the same time each day. This routine can help you get back to your normal number of bowel movements.

- Keep a record of your bowel movements. Showing this record to your health care team and talking to them about what is normal for you can help your doctor treat the constipation you are experiencing.

- Talk with your doctor about dietary fiber. High-fiber foods and fiber supplements can make constipation worse for some people. Ask your doctor if adding fiber to your diet will help relieve constipation for you.

What can people with cancer take for constipation?

Your doctor may prescribe medicines called laxatives that help prevent or relieve constipation. Use only medicines and treatments for constipation that your doctor recommends. Many different types of laxatives are available, and your doctor may recommend others not listed here:

- Osmotics pull water into the bowel from other parts of the body, making it easier to have a bowel movement. Polyethylene glycol (MiraLAX), magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia), lactulose (Enulose), and sorbitol are examples of osmotic laxatives.

- Stool softeners, or emollients, soften poop by increasing the amount of water and fat that the poop absorbs. Docusate (Colace) is an example of a stool softener.

- Stimulant laxatives cause the intestines to contract so stool moves through the bowel. Bisacodyl (Correctol), senna (Senokot), and castor oil are examples of stimulant laxatives.

Do not use suppositories (capsules you insert into your anus) or enemas (liquid medicine that you inject into your anus) unless your doctor recommends them. In some people with cancer, these treatments may lead to bleeding, infection, or other harmful side effects.

How a caregiver can help

- Encourage the person you are caring for to drink plenty of water or other fluids. Make sure they also have access to hot beverages and prune juice, which may help relieve constipation.

- Help the person you are caring for stay physically active. Physical activity includes moving from a bed to a chair, walking short distances, or riding an exercise bike. Talk to their care team to find out what exercise is right for them.

- Monitor the person's bowel movements and help them keep a record of their bowel movements. They should have a bowel movement every day or every other day that is not hard and does not require straining.

- Notify the care team if the person has had fewer than three bowel movements in one week or is experiencing severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and other signs of fecal impaction.

What is fecal impaction?

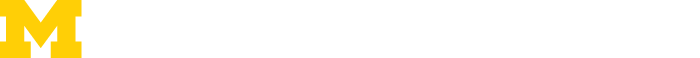

Fecal impaction is a serious condition in which hardened stool blocks the colon or rectum. Unlike constipation, fecal impaction can be life-threatening and requires immediate medical attention.

Long-term constipation can lead to fecal impaction, a potentially life-threatening condition in which hardened stool blocks the flow of waste through the colon or rectum. Fecal impaction requires immediate medical attention.

What causes fecal impaction?

Causes of fecal impaction include:

- opioid pain medicines

- little or no physical activity over a long period

- dietary changes

- constipation that is not treated

- inability to push stool out because of weakness or muscle problems

What are signs and symptoms of fecal impaction?

Signs and symptoms of fecal impaction include:

- chronic constipation

- a feeling of pressure in the rectum or incomplete emptying of stool

- lower back pain or pain in the abdomen

- urinating more or less often than usual or being unable to urinate

- breathing problems, rapid heartbeat, confusion, dizziness, low blood pressure, and bloating

- sudden, explosive diarrhea or leaking stool (as stool moves around the impaction)

- nausea and vomiting

- dehydration

How is fecal impaction diagnosed in people with cancer?

Fecal impaction is diagnosed in the same way as constipation. To learn more, go to How is constipation diagnosed in people with cancer?

How is fecal impaction treated?

The main treatment for fecal impaction is to moisten and soften the stool using an enema. The softened stool can then pass out of the body. Because enemas can be dangerous for people with cancer, they should be used only when prescribed and given by a doctor.

You may need to have stool manually removed from the rectum after it is softened. Laxatives are generally not used to treat fecal impaction because they may cause cramping and damage to your intestines.

Talking with your doctor about constipation

Tell your doctor or nurse if you are having constipation so you can get treatment as soon as possible. Treating constipation early can help prevent serious problems like fecal impaction and bowel obstruction. Your doctor can help you find ways to treat and manage this side effect of cancer and cancer treatment.

Questions to ask your provider about constipation:

- What symptoms or problems should I call you about?

- Should I take medicine for constipation? If so, what medicine should I take? What medicine should I avoid?

- How much liquid should I drink each day?

- What foods can help with constipation? What foods should I avoid?

- Could I meet with a registered dietitian to learn more?

Getting support if you have constipation

Side effects like constipation or fecal impaction can be hard to deal with, both physically and emotionally. It's important to ask for support from your health care team. They can help you prepare for and make it through difficult times. Learn more about ways to cope with cancer, including ways to adjust to daily life during cancer treatment.

For family members and friends who are caring for someone with cancer, you may find these suggestions for caregivers to be helpful.

Related Resources

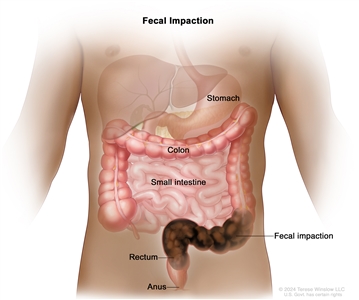

A bowel (intestinal) obstruction is a serious condition that occurs when the small or large intestine becomes blocked. The blockage stops food and stool (poop) from moving through the intestines. The intestine may be partly or completely blocked and can sometimes be blocked in two places. Bowel obstructions can be life-threatening and require immediate medical attention.

A bowel obstruction may occur soon after cancer treatment ends or many months or years later. Bowel obstruction is most common in people with advanced cancer.

What causes bowel obstruction in people with cancer?

Bowel obstruction in people with cancer may be caused by:

- Cancer treatment. Some types of cancer treatment can cause bowel obstruction:

- Surgery on the abdomen or pelvis may lead to scar tissue, also called adhesions, that form after surgery. Adhesions can cause the intestines to bind together, creating a blockage.

- Radiation therapy directed at the abdomen can damage the intestines, leading to scar tissue, inflammation, radiation enteritis, and irritation that can block the bowel.

- Cancer itself. Cancers that form in the abdomen, such as colon, ovarian, pancreatic, or stomach cancer, are more likely than other cancer types to cause a bowel obstruction. A bowel obstruction caused by cancer itself is called a malignant bowel obstruction. Cancer can cause a bowel obstruction in different ways:

- A tumor that forms in or presses on the bowels can cause a bowel obstruction. A tumor can also cause a bowel obstruction if it grows in an area that affects the nerves that control the movement of food through the intestines.

- Advanced cancer can cause a bowel obstruction when cancer spreads to the bowels from another place in the body. Advanced cancer is the most common cause of malignant bowel obstruction.

A malignant bowel obstruction happens when a tumor forms in the intestines and blocks the flow of waste. The tumor may be from colon or rectal cancer or from cancer that has spread to the intestines from another part of the body.

Other causes of bowel obstruction not related to cancer or cancer treatment include a twist in the intestine, a hernia, irritable (inflammatory) bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, some medicines, long-term constipation, and other conditions.

What are the signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction?

Signs and symptoms of a bowel obstruction include:

- abdominal pain or cramps

- swelling in the abdomen

- constipation

- diarrhea

- nausea or vomiting

- problems passing gas

- loss of appetite

When an obstruction starts, the intestines may be partly blocked, causing a few mild symptoms. As the obstruction gets worse, your symptoms may happen more often and become more severe. You may have frequent vomiting, extreme bloating, and intense abdominal pain. These are signs of a complete obstruction, in which stool and gas are mostly or totally blocked from leaving the body.

How is bowel obstruction diagnosed?

Finding the cause of a bowel obstruction and the place where the intestine is blocked is important so your doctor can recommend treatment. Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and do a physical exam. They may also use the following tests and procedures to diagnose a bowel obstruction and suggest treatment options:

- CT scan (CAT scan) uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This scan helps doctors find the cause and exact location of the obstruction. It is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Abdominal x-ray is an x-ray of the organs inside the abdomen. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. It can also show the location of the obstruction, but it is not as sensitive as a CT scan.

- Blood tests, such as a complete blood count and electrolyte panel, show if you are dehydrated or have an electrolyte imbalance or infection. These problems may be caused by a bowel obstruction.

- Urinalysis checks the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells. A urinalysis shows your fluid levels, signs of infection, and other problems that may be caused by a bowel obstruction.

Treating a bowel obstruction

If you have a bowel obstruction, you will need to be treated in a hospital. Treatment for a bowel obstruction depends on what caused the blockage and whether the intestines are partly or completely blocked. If you have a complete blockage, you will probably need surgery. Partial obstructions may clear up with nonsurgical treatments.

Treatment for a bowel obstruction may include:

- Bowel rest. This is when you avoid eating and drinking to keep the obstruction from getting worse. Bowel rest or a liquid diet that is easy on your intestines can help your body clear the blockage. You may also receive fluid replacement therapy (IV fluids) to help the fluids and electrolytes in your body return to normal.

- Nasogastric tube. This tube is inserted through the nose and esophagus into the stomach to relieve pressure caused by a bowel obstruction by removing fluid and gas from the digestive system. A nasogastric tube helps control nausea, vomiting, and pain related to the obstruction and may help your body clear the blockage.

- Stent. This is a tube placed in the intestine to open the blocked area. Stents relieve bowel obstruction symptoms by temporarily opening the bowels to let food, waste, and gas pass through the body. Stents are most often used to treat bowel obstructions caused by cancer, but they may also be used for obstructions with other causes.

- Surgery. If a bowel obstruction does not go away with other treatments or if you have a complete blockage, you may need surgery to remove the obstruction. For an obstruction caused by cancer, surgery will include removing the tumor that is causing the blockage. Your doctor will talk with you about your overall health and potential risks and benefits of surgery to help you decide if surgery is right for you.

- Gastrostomy tube. A tube that helps release fluid and air from the stomach to relieve symptoms caused by the obstruction. A tube is inserted through the wall of the abdomen directly into the stomach. The gastrostomy tube can be attached to a drainage bag with a valve. When the valve is open, fluid and air can leave the stomach. Gastrostomy tubes are most often used to treat bowel obstructions caused by cancer.

- Antibiotics. Sometimes a bowel obstruction causes a tear in the intestines that lets fluids leak into the abdomen. These fluids can cause your body to have an extreme immune response to an infection (sepsis). Antibiotics can help prevent tissue damage, organ failure, or death from sepsis.

- Antinausea and pain medicines. These can treat or control nausea, vomiting, and pain caused by a bowel obstruction.

Considerations for treating a malignant bowel obstruction

If you have a bowel obstruction caused by cancer (also called malignant bowel obstruction), talk to your health care team about available treatments and your goals of care. In most cases, treatments for malignant bowel obstructions relieve symptoms and improve quality of life but may not help you live longer from cancer. You and your family may need to make difficult decisions about your care at this time. If you choose care meant to relieve symptoms over more aggressive treatments, you can learn more about Choices for Care When Treatment May Not Be an Option.

Talking with your doctor about bowel obstruction

If you think you have a bowel obstruction, contact your doctor right away. They can help you decide on a treatment that is right for you.

Questions to ask your provider about bowel obstruction:

- What is causing the bowel obstruction?

- What treatments are available to me?

- What are possible complications of treatments I may receive for bowel obstruction?

- What foods should I eat or avoid?

- How much liquid should I drink each day?

- What symptoms or problems should I call you about?

- Will I be at risk of future bowel obstructions?

Getting support if you have a bowel obstruction

Side effects like bowel obstruction can be hard to deal with, both physically and emotionally. It's important to ask for support from your health care team. They can help you prepare for and make it through difficult times. Learn more about ways to cope with cancer, including ways to adjust to daily life during cancer treatment.

For family members and friends who are caring for someone with cancer, you may find these suggestions for caregivers to be helpful.

How a caregiver can help

- Help the person you are caring for eat and drink the foods and liquids their doctor has recommended. Many people treated for a bowel obstruction will need to be on a liquid diet while they recover.

- Provide the person you are caring for with a heating pad for their belly that can help relieve pain and cramping.

- Talk with the person you are caring for about their goals of care, especially if they have a malignant bowel obstruction, to help them decide on a treatment that is right for them.

- Carefully review follow-up care with the person's doctor to learn what to expect after treatment and how you can help.

Related Resources

Diarrhea means having bowel movements (stools) more often than normal. The stool may also be soft, loose, or watery. Diarrhea is a common side effect of many cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy.

When you have severe diarrhea, your body does not absorb enough water and nutrients. This can lead to serious health problems such as dehydration. Dehydration can be life-threatening, so tell your doctor or nurse if you have diarrhea.

Your doctor will find the diarrhea's cause and recommend ways to feel better, which may include medicines and food that help decrease or stop diarrhea.

What causes diarrhea in people with cancer?

Frequent diarrhea may be a sign or symptom of cancer or a side effect of cancer treatment. Causes of diarrhea in people with cancer include:

Causes from cancer and cancer treatments

- Certain types of cancer. Diarrhea can be a symptom of some cancers that form in the abdomen or the digestive tract. Cancers that may cause diarrhea include colon cancer, rectal cancer, neuroendocrine tumors in the digestive tract or thyroid, lymphomas that start in the digestive tract, and pancreatic cancer.

- Chemotherapy. Many types of chemo can cause diarrhea because they destroy not only cancer cells but also rapidly dividing healthy cells, including those that line your digestive tract.

- Immunotherapy. Some immunotherapy drugs, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors, can cause inflammation. An inflamed colon (colitis) can lead to diarrhea.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation directed at the abdomen, pelvis, or rectum can cause diarrhea by damaging healthy tissue in the digestive tract. Diarrhea from radiation therapy is a symptom of radiation enteritis.

- Surgery. Having surgery to the esophagus, stomach, gallbladder, or bowel (intestine) can cause diarrhea.

- Targeted therapy. Diarrhea is a common side effect of many targeted therapy drugs.

- Bone marrow or stem cell transplant. Medicines and radiation given during these treatments may cause diarrhea. Diarrhea after bone marrow or stem cell transplant may also be a symptom of graft-versus-host disease.

Other causes

- Stress and anxiety. Being diagnosed with cancer and undergoing treatment often leads to stress and anxiety, which are common triggers for diarrhea. Learn about ways to manage stress and anxiety.

- Medicines. Diarrhea can be a side effect of some medicines, including antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Drugs used to treat diabetes, depression, mood disorders, and heartburn may also cause diarrhea.

- Supplements and herbal products. Some supplements can cause diarrhea. Tell your health care team if you are taking any supplements or herbal products or if you start a new supplement.

- Infections. Infections are a common cause of diarrhea. When being treated for cancer, you are more vulnerable to viral and bacterial infections, including foodborne illness, because treatments such as chemo can weaken your immune system.

- Other conditions. Irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, fecal impaction, and food allergies can all cause diarrhea.

Symptoms and grades of diarrhea

Signs and symptoms of diarrhea include:

- having soft, loose, or watery stools

- having bowel movements more often than normal

- feeling an urgent need to have a bowel movement that is difficult to control

- stomach pain or cramps

- excessive gas

People with diarrhea may also:

- have blood or mucus in the stools

- feel dizzy or lightheaded

- have a fever

- experience weight loss

Your doctor will talk with you about your symptoms to figure out the severity, or grade, of your diarrhea. Grade is based on how many bowel movements you have per day, relative to your normal number of bowel movements. Grades 1 and 2 (having up to six bowel movements above your normal daily number) can usually be managed at home, but grades 3 and 4 (having seven or more bowel movements above your normal daily number) can be life-threatening and may require treatment in a hospital.

How is diarrhea diagnosed in people with cancer?

Finding the cause of diarrhea is important so you can get relief before it interferes with your cancer treatment or causes life-threatening dehydration. Your doctor may ask questions such as:

- How many bowel movements have you had in the past day?

- What was your last bowel movement like (how much, how hard or soft, what color, was there blood or mucus)?

- Have you had any dizziness, fever, or weight loss?

- What are you eating and drinking each day?

Your doctor will do a physical exam and may also use tests and procedures to diagnose the cause of diarrhea and suggest treatment options:

- Stool tests: Tests that check the stool for blood, viruses, bacteria, and other issues that may cause diarrhea.

- Blood tests: These include a complete blood count, electrolyte panel, kidney function test, and albumin test that are used to find the cause of diarrhea and determine its severity.

- Urinalysis: A test to check the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells.

- Digital rectal exam: A test in which your doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for anything that seems unusual.

Ways to treat and control diarrhea

Treatment of diarrhea in people with cancer depends on its cause and severity (grade). Your doctor may suggest changes to your diet and prescribe medications. You may also receive intravenous (IV) fluids to help replace the fluids you lost. If chemo is causing severe diarrhea, your doctor may reduce your dose or have you stop taking it until your diarrhea gets better.

Tips for managing diarrhea

- Drink lots of water or other fluids. Ask your doctor or nurse how much fluid you should drink. Drinking clear liquids, such as water or broth, helps replace fluids and electrolytes your body loses when you have diarrhea. Room temperature liquids are easiest on the stomach.

- Eat small meals. It may help to eat frequent small meals or snacks throughout the day, instead of three larger meals.

- Eat low-fiber foods. Eating foods that are low in fiber can help reduce diarrhea. Foods such as white bread, pasta, and canned fruit are good choices.

- Eat foods that are high in sodium and potassium. You lose these minerals when you have diarrhea, so it's a good idea to eat foods that help replace them. Peeled and boiled potatoes, soup, bananas, applesauce, and crackers are good options.

- Avoid foods and drinks that can make diarrhea worse. These include alcohol, milk and dairy products, spicy foods, caffeinated drinks, dried beans, foods high in fat, fruit juices, and sugar-free gum or candies. Learn more about how changing your diet can help you manage side effects of cancer treatment at Nutrition During Cancer Treatment.

- Keep your anal area clean and dry. Try using warm water and baby wipes to stay clean. Taking a sitz bath—a warm, shallow bath—can also be soothing to your anal area.

- Keep a record of your bowel movements. Show this record to your health care team and talk to them about what is normal for you. This can help your doctor treat the diarrhea you are having.

Medicines for diarrhea

For severe diarrhea that happens while you are getting cancer treatment, your doctor may recommend medication. Your doctor may prescribe loperamide (Imodium) or a combination of diphenoxylate and atropine (Lomotil) to prevent or treat diarrhea. Doctors may also recommend probiotics that help with digestion and bowel function or fiber supplements (e.g., Metamucil). Check with your doctor before taking these or other medicines and supplements.

How a caregiver can help

- Encourage the person you are caring for to drink water or other fluids their doctor suggests. Make sure they have a water bottle they can carry and refill throughout the day.

- Keep a record of the person's bowel movements. Ask the health care team about when you should call them if the diarrhea lasts or becomes more severe.

- Try to keep the person's pantry stocked with foods that can help relieve diarrhea.

- Encourage the person to take warm, shallow baths to relieve pain and irritation from diarrhea.

Talking with your doctor about diarrhea

Tell your doctor or nurse if you are having diarrhea. They can help you find ways to prevent and control this side effect of cancer and cancer treatment.

Questions to ask your provider about diarrhea:

- What symptoms or problems should I call you about?

- What medicines can I take for diarrhea?

- What can help decrease rectal pain and irritation?

- How much and what types of liquid should I drink each day?

- What foods should I eat while I have diarrhea? What foods should I avoid?

- Could I meet with a registered dietitian to learn more?

Getting support if you have diarrhea

Side effects like diarrhea can be hard to deal with, both physically and emotionally. It's important to ask for support from your health care team. They can help you prepare for and make it through difficult times. Learn more about ways to cope with cancer, including ways to adjust to daily life during cancer treatment.

For family members and friends who are caring for someone with cancer, you may find these suggestions for caregivers to be helpful.

Listen to tips on how to manage diarrhea caused by your cancer treatments such as radiation therapy. (Type: MP3 | Time: 2:55 | Size: 2.7MB)

Related Resources

- Gastrointestinal Complications (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

- Eating Hints: Before, During, and After Cancer Treatment

Last Revised: 2024-10-23

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.