Anomalous left coronary artery (ALCA) occurs when the left coronary artery, which carries blood to the heart, is connected to the pulmonary artery instead of the aorta. It is a rare problem, comprising less than 1% of all congenital heart defects in children.

The University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital is home to one of the nation’s top congenital heart programs, with expertise in caring for children with anomalous left coronary artery as well as the full range of congenital heart defects. We offer state-of-the-art treatment and management of ALCA, as well as a comprehensive range of support services and long term follow up for children and their families. Learn more about the Congenital Heart Center.

- What is anomalous left coronary artery?

- How is anomalous left coronary artery diagnosed?

- How is anomalous left coronary artery treated?

- What are the long-term health issues for children with anomalous left coronary artery?

What is anomalous left coronary artery?

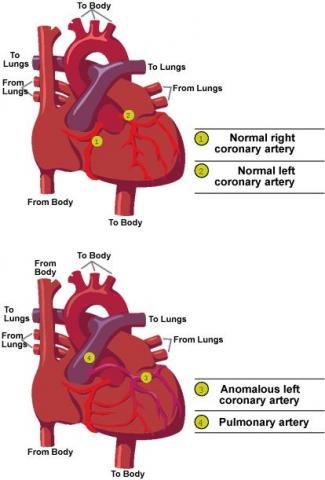

The coronary arteries are the blood vessels that supply the heart muscle with red or oxygen-rich blood. There are usually two primary coronary arteries that arise from the aorta, one from the right side (1) and one from the left side (2). Sometimes, for unknown reasons, when the heart and blood vessels are forming, the left coronary artery (3) is connected to the pulmonary artery (4), instead of the aorta.

Right after birth, the pressure in the pulmonary artery is high so that enough blood flows through this vessel to supply the heart muscle with oxygen. Over the first two months of life, however, the pressure in the pulmonary artery drops and so does the forward blood flow through this vessel.

When the left coronary artery connects with the pulmonary artery, it may actually carry blood in reverse, stealing blood away from the heart. When the heart does not get enough oxygen-rich blood from the coronary arteries, it begins to fail, in a manner similar to what is seen in patients with myocardial ischemia or infarction (“heart attack”).

Diagnosing anomalous left coronary artery.

In patients with anomalous left coronary artery, the heart is not able to pump as much blood as the body needs. This causes symptoms of congestive heart failure such as poor feeding, clammy sweating, lethargy, rapid breathing and heart rates, and poor growth. Often these symptoms are seen between 2 and 6 months of age, but they can occur during early infancy or rarely, during later childhood. In older children, there may also be swelling around the eyes and/or feet. Often a heart murmur is present.

The electrocardiogram is usually abnormal. On chest x-ray, the heart is usually quite enlarged. The definitive diagnosis is usually made by an echocardiogram. Sometimes, additional tests such as CT, MRI, or a heart catheterization may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of anomalous left coronary artery.

Anomalous left coronary artery is a serious problem and requires surgery as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made. The aim of surgery is to connect the ALCA with the aorta. The precise surgery depends on the exact location of the ALCA. Sometimes, it can be moved, along with a button of tissue, from the pulmonary artery and sewn into the aorta. If the ALCA is located too far away from the aorta to move, a "tunnel" is made from the aorta to the ALCA.

Long term effects of anomalous left coronary artery.

The long-term health effects on children with anomalous left coronary artery vary depending on the degree of damage to the left ventricle. If the problem was found early, before much damage occurred, and the surgery was successful, there are few long-term health effects. If the left ventricle was damaged, there may be ongoing symptoms of congestive heart failure. As a result, the child may have low stamina, and may need to be restricted from sports. These symptoms are often treated with medicines such as digoxin, diuretics, blood pressure lowering medicines, and/or blood thinners. If the damage is very severe, a heart transplant may be considered.

Bacterial Endocarditis: Children with congenital heart disease are at slightly increased risk for a type of bacterial infection called subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). Children with heart defects are more prone to this problem because of the altered flow of blood through the heart and/or abnormalities of the valves. Antibiotics are sometimes prescribed to prevent SBE. Your pediatric cardiologist will tell you whether your child needs this protection, which is often referred to as SBE prophylaxis, before and after dental or surgical procedures.

Exercise guidelines: An individual exercise program is best planned with the doctor so that all factors can be included. In children with ALCA, sports guidelines are based on the degree of heart damage. If there is some damage, children are usually restricted from vigorous or competitive sports but can participate in recreational sports. It is important for them to be able to self-limit their activity, that is, to rest whenever they feel the need to do so. The children can usually participate in gym class but should be allowed to self-limit their level of exertion and they should not be graded (which could increase the pressure to exceed their natural limits).

Neurodevelopmental delays: Research shows that children who undergo cardiac surgery during the first year of life are at higher risk for developmental, learning, and/or behavioral concerns later in life. Continued evaluation for these children is highly recommended to ensure early identification of delays. The C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital Congenital Heart Center Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up Program offers a complete developmental assessment and referral program to ensure early intervention and support for children experiencing neurodevelopmental delays, and provide a solid foundation for later learning and future development.

Take the next step

The University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital Congenital Heart Center is a leader in treatment of anomalous left coronary artery. For more information on our programs and services, or to make an appointment, please call 734-764-5176.